Eugene is Syrian’s safe haven

Sitting outside a downtown Eugene coffee shop on Pearl Street in late October, he speaks in slow and careful English, a language still as foreign to him as the city, state and country that are now his home.

“It was the worst day in my life,” Ali Turki Ali says of June 24.

It was not only the day that Ali, 34, left family members behind in Turkey as he flew from Istanbul to Los Angeles; it was also the day fighters with the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, killed one of his nine sisters and her husband in Syria, the homeland he may never see again.

After the 14-hour flight, Ali spent four hours being questioned by the International Organization for Migration at Los Angeles International Airport.

The questioning in Los Angeles was a routine procedure for an incoming immigrant or refugee — he already had undergone a 14-month process of questioning by United Nations and U.S. officials while in Turkey — but it still caused him to miss his connecting flight to Portland.

After an IOM official took him to an Los Angeles area hotel (he would fly to Portland on June 25, en route to Eugene), he saw the horrifying news on his brother Mohamed’s Facebook page: Their older sister, Shemsa, and her husband, Bozan, had been slaughtered by ISIS in a house-to-house rampage, along with about 250 others in the Syrian border town of Kobani.

“After I lost my sister, I don’t think anyone will go back to Syria,” says Ali, sitting in his Eugene apartment last Monday. “Especially my niece and my nephew. They lost their mom. She was killed. Why would they go back to Syria?”

Ali, who was a high school math teacher in Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, and is studying English in Lane Community College’s English-as-a-Second-Language program, is one of just six Syrian refugees who have come to Oregon — five of them this year — since civil war erupted in their country in 2011, according to U.S. State Department numbers.

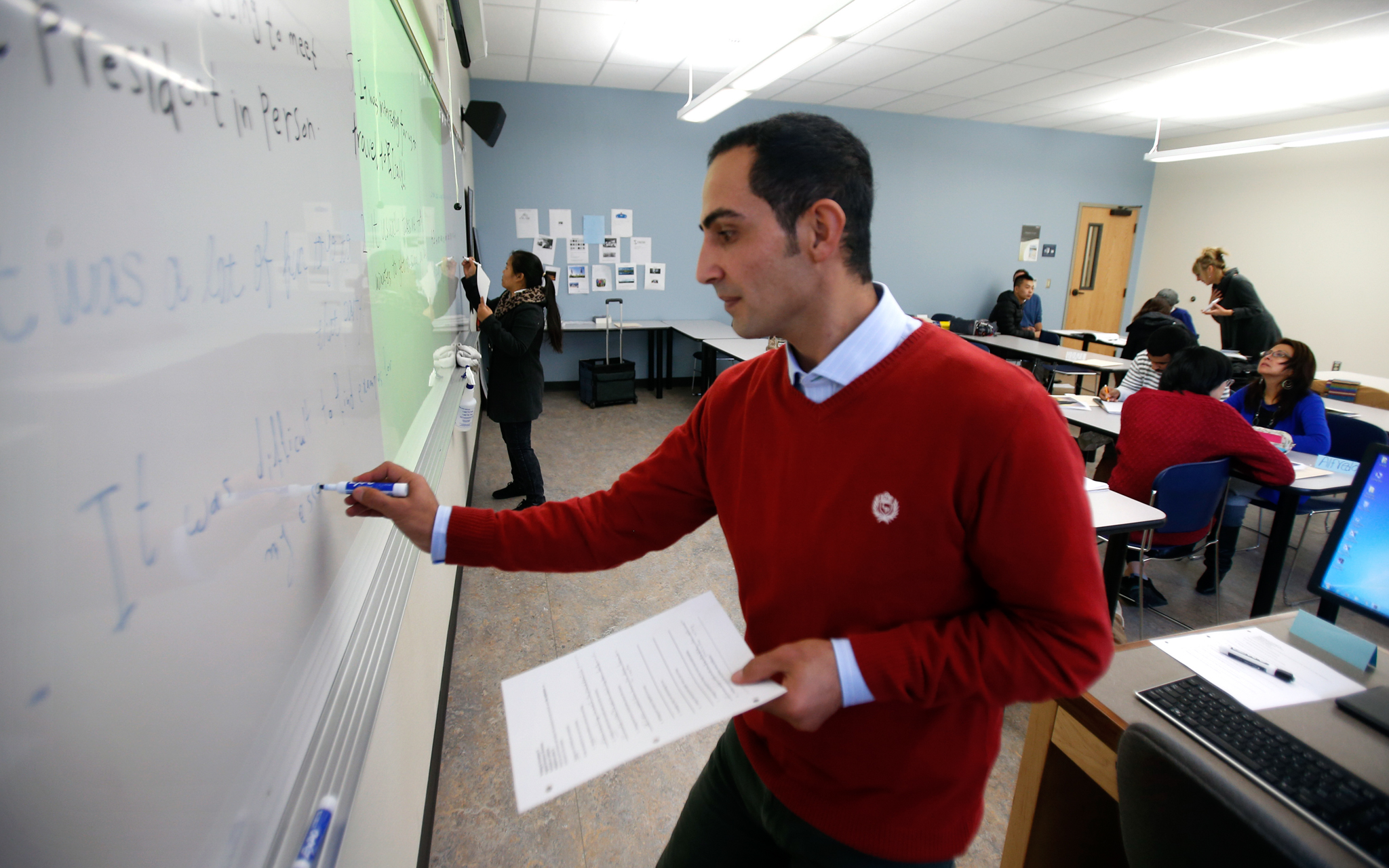

Ali writes a sentence on the white board at the front of hi English class at Lane Community College in Eugene on Tuesday, November 17, 2015. Not being able to communicate sometimes leads to feelings of isolation for Ali and he is working hard to learn to speak English. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard)

Ali writes a sentence on the white board at the front of hi English class at Lane Community College in Eugene on Tuesday, November 17, 2015. Not being able to communicate sometimes leads to feelings of isolation for Ali and he is working hard to learn to speak English. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard) Ali, second from left, works on a group assignment with Rossi Ramirez-Radillo from Mexico, Qi Zhang from China, and Wahab from Saudi Arabia, in his English class at Lane Community College in Eugene on Tuesday, November 17, 2015. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard)

Ali, second from left, works on a group assignment with Rossi Ramirez-Radillo from Mexico, Qi Zhang from China, and Wahab from Saudi Arabia, in his English class at Lane Community College in Eugene on Tuesday, November 17, 2015. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard) Ali dishes up dinner for guests at a dinner Eugene on Sunday, November 22, 2015 as Baker arrives for a dinner. Ali prepared braised lamb in yogurt sauce for a group of relatives of Peter Ward. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard)

Ali dishes up dinner for guests at a dinner Eugene on Sunday, November 22, 2015 as Baker arrives for a dinner. Ali prepared braised lamb in yogurt sauce for a group of relatives of Peter Ward. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard) Ali hugs Peter Ward goodbye at the end of the evening in Eugene on Sunday, November 22, 2015. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard)

Ali hugs Peter Ward goodbye at the end of the evening in Eugene on Sunday, November 22, 2015. (Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard)

Only 2,280 Syrian refugees have made it to the United States since the war began, according to the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. The vast majority, about 2,000, have arrived in the past year.

In September, under pressure from aid groups who cite the numbers of Syrian refugees accepted by European nations such as Germany (a reported 800,000), President Obama said the United States would accept 10,000 or more Syrian refugees in the 12 months beginning Oct. 1,

The Oregon Department of Human Services says it has only one Syrian refugee listed as receiving temporary government financial aid. The department cannot legally name that person, spokesman Gene Evans says.

Ali, however, says he is receiving the minimum eight months’ assistance in federal funding — $339 a month in federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families and $194 in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — through the state Department of Human Services. He also says he is covered by the Oregon Health Plan, the government-funded health insurance system, during his first eight months in the state.

Once the United States approves and accepts a refugee, as it has Ali, it extends financial help to try to ease the refugee’s path into work, housing and permanent residency.

For Ali, the trek from Syria to find a new home in a stable country has taken years, much of it waiting in Turkey. The process has included innumerable interviews with officials who screen refugees and try to line them up with host countries. Vetting by U.S. officials lasted more than a year.

“It’s bad news”

For Ali, the question now is whether his mother, stepmother, two brothers and their families, who have not yet found a nation to take them as refugees, will be able to join him in the United States.

The Nov. 13 terrorist attacks in Paris, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, has stirred an anti-refugee, anti-Muslim backlash in the United States, especially among Republican governors and members of Congress. A Syrian passport was found near one of the suicide bombers in that attack, and the passport’s holder was registered as a refugee in Europe — though fake Syrian passports are widely available in Turkey, according to Human Rights Watch.

On Nov. 18, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, said Oregon would continue to accept refugees from Syria and elsewhere.

“The words on the Statue of Liberty apply in Oregon just as they do in every other state,” Brown said. “The Syrian people will deal with the realities of war for the rest of their lives and for generations to come. As Oregonians, it is our moral obligation to help them rebuild their lives.”

But on Nov. 19, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 289-137 — including “yes” votes by Oregon Reps. Kurt Schrader, a Democrat, and Greg Walden, a Republican — to drastically tighten screening on Syrian refugees.

The White House said Obama would veto the bill if the Senate votes in favor of it.

“It’s bad news, because my family is waiting … to come here,” Ali says during a hike up Spencer Butte in south Eugene with Peter Ward, a University of Oregon graduate student who is serving as Ali’s U.N.-approved sponsor.

Ali’s mother, Amina; stepmother, Faiza; and two brothers and their families, including a 4-year-old nephew, Jan (pronounced “John”), have been in Gaziantep, Turkey, a city of 1.5 million just across the border from Syria, since fleeing their country two years ago. Ali lived with them in an apartment there for 15 months, from March 2014 until leaving for the United States in June.

Jan is the son of Ali’s brother, Mahmoud. Ali says Jan suffers from xeroderma pigmentosum, a rare genetic intolerance to sunlight that can cause skin cancer and blindness. Children with the condition are sometimes called “moon children” because they can only be outside after the sun goes down.

Ali told U.N. officials in the Turkish capital, Ankara, about his nephew Jan last year. Three officials later visited the boy in Gaziantep and began a file for him, Ali says.

At Ali’s initial interview last year with U.N. officials in the Turkish capital of Ankara, he told them about Jan. Three officials later visited the boy in Gaziantep and began a file for him, Ali says.

Ali wants to get Jan out of Turkey and to the United States, perhaps to Sacramento, which has a population of children with the disease as well as an xeroderma pigmentosum family support group.

“It’s too far away”

As he walks the trail leading up Spencer Butte last weekend, Ali is asked what he thinks some Americans fear from Syrians. He ponders: “Maybe they think all (Syrians are part of) ISIS? Maybe they think all (Syrians) like ISIS?”

Ward, 25, asks Ali if he worries about a negative reaction once word spreads that he’s in Eugene.

“I think maybe some people don’t like that,” says Ali, whose English has improved rapidly in the five months he’s been here. “But I think most people in Eugene are friendly. Maybe 0.1 percent” would disapprove of him, he says.

Ali had never heard of Oregon, let alone Eugene, until he met Ward’s father, Mark Ward, last year in Turkey.

A longtime State Department employee, Mark Ward has been director of the Syrian Transition Assistance and Response Team based at the U.S. Embassy in Ankara since November 2012. The team is responsible for coordinating U.S. assistance to Syria from Turkey. Two million Syrians have fled to Turkey in recent years.

Ali met Mark Ward in April 2014 at a U.N. refugee agency in Gaziantep, where the 60-year-old diplomat often visits.

Ali wanted to migrate to Europe, maybe Germany or Denmark, where two of his five brothers are. But those nations’ refugee quotas, like Turkey’s, had been met, Mark Ward said by phone from Turkey.

“But there is a country taking refugees,” Ward recalls telling Ali last year.

“Who is?” Ali said.

“The United States,” Ward said.

“And he got this very sad look on his face,” Ward says.

“It’s too far away,” Ali said.

“You will need a sponsor wherever you go,” Ward said.

“I know one American,” Ali said. “You. And you’re not in the United States.”

“I know an American who could be your sponsor,” Ward said. “My son, Peter.”

A sponsor is someone who agrees to watch over a refugee for their first six months in the country. The sponsor helps a refugee find a place to live and learn about the community.

Mark Ward showed Ali a map of Oregon. It might as well have been a photograph of Mars.

“And that same look came over his face,” Ward says.

“And then I had to convince (Lutheran Community Services) in Portland that I wanted him in Eugene, and that wasn’t easy,” Ward says. Lutheran Community Services is Ali’s receiving agency in Oregon and one of three refugee resettlement agencies in the state, according to Evans, the state DHS spokesman.

“We want him in Portland,” Ward recalls the agency saying. “Where we can keep an eye on him.”

Ali’s $983 plane flight from Istanbul to Portland was paid for by the Lutheran Immigration & Refugee Service, according to his paperwork. He is repaying it in $35 monthly installments.

Born in a village

Ali was born in a village outside Kobani, in the winter of 1981. He is one of the youngest of 15 siblings born to the same father, the late Turki Ali, a farmer who was married four times.

The family moved to Manbij, about 35 miles southwest, when he was 2. When Ali was 4, his father was killed in a car crash. Seven of his nine older sisters were already married, so he was raised by his mother, Amina, and his stepmother, Faiza, and surrounded mostly by his older brothers.

The family was not wealthy but owned land that his father had farmed, Ali says.

He finished high school in Manbij, an ancient city of about 100,000.

He studied mathematics at Aleppo University, earning his undergraduate degree in 2005 and a graduate degree in 2008. Then he began to teach.

But in the summer of 2012, the war that has now killed more than 250,000 people came to Aleppo.

More than three years later, various groups, including the Syrian Army, rebel forces, ISIS, Kurds, Sunni militants, the Lebanese Shiite group Hezbollah and, more recently, Russian forces, continue to battle for control. The fighting has caused catastrophic destruction to the Old City of Aleppo, the city center constructed between the 12th and 16th centuries, according to news reports.

Ali lived among this chaos for almost two years before fleeing. His school, where he taught 35 to 40 students each day in calculus, algebra and statistics, was a 15-minute walk from his apartment.

“One day I was in class,” he recalls. “Suddenly, we heard a bomb. It makes the students crazy. Everybody wants to go, but you can’t leave them. So we close the (school) door and take them to the first level.”

After 30 minutes, students were allowed to go home.

A decisive move

Eighteen months of military service is compulsory for young men in Syria after they turn 18. Ali says he served in the Syrian Army from September 2008 to March 2010.

But as the war has raged on, young Syrians have been called back to duty, to fight against the rebels, Ali says. It’s not optional. Syrian forces will come to your home and take you against your will, he says.

“Very dangerous to leave (Syria),” Ali says. “If they found me, they would take me to military.”

This is why he left, he says, long after most of his family had already fled.

He said he was tipped by a friend in the Syrian government that the military was due to visit him on March 2, 2014.

He fled that day, he says. He took virtually nothing with him, except his keys and a small bag.

Later, his roommate confirmed military officers knocked on his door later that day.

Ali took a bus to Manbij, about 50 miles northeast of Aleppo, where a sister lived, and stayed there three days. A nephew drove him north to Kobani, where he stayed a few days with his brother, Ahmed, who is now a refugee in Germany.

Ahmed arranged for Ali to get a ride to the border with a driver who was taking about 15 others.

They would need to find a spot in the border to cross illegally — and the driver knew of one. Ali paid the driver 5,000 lira, about $20 in U.S currency.

He and the others left the van and walked a couple of kilometers, in broad daylight, to a spot at the border where a hole had been cut through the high barbed wire fence.

The driver had arranged for another driver, on the Turkish side, to pick them up.

The new driver “took us to his home,” Ali says, in a small city near the border. “We wash, we clean a little.”

Then he took them to a bus station to buy a ticket for the short trip to Gaziantep to meet his family.

A new life

“He didn’t want to go back (to Syria), and he wasn’t comfortable in Turkey,” says Mark Ward, who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and married his late wife, Maryruth “Mimi” Vollstedt, a 1972 graduate of Coos Bay’s Marshfield High School, in Eugene in 1987.

The convoluted process to gain refugee status in the United States can take two or more years. Ali’s connection with Mark Ward got him to this country in about 14 months.

His first interview with U.N. officials in Ankara took place in July 2014. Ankara is a 12-hour bus ride from Gaziantep.

He had two three-hour interviews, with two different officials, asking why he left Syria and why he couldn’t go back.

To be accepted into the United States, a refugee’s name is run through law enforcement and intelligence databases for terrorist or criminal history; they go through three separate fingerprint screenings; they are screened against FBI and Homeland Security databases, and checked against data collected by the Defense Department during operations in Iraq, according to news reports.

After his U.N. interviews, Ali was matched with an American resettlement agency, the International Catholic Migration Commission, or ICMC. He traveled twice to Istanbul, a 16-hour bus ride each way, for more interviews.

In February, he went to Istanbul again, by plane this time, for a day of medical tests and three days of more questioning and preparation.

Then, he waited.

In March, he first met Peter Ward — who grew up around the world because of his father’s State Department work — via the videochat application Skype. Ward was in Moscow, where he had lived, worked and studied Russian, which he now studies and teaches at the UO as a graduate teaching fellow.

In May, an ICMC official called Ali in Gaziantep with the news.

“They told me I would go to U.S. on June 24,” he says.

His reaction?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I was happy to go to U.S. But, also, I was sad I would leave my family. Maybe I could start a new life? Maybe I could begin again?”

A new family

Last Sunday, Ali cooked braised lamb in a yogurt gravy for Peter Ward and members of his mother’s extended family at the Jefferson Westside neighborhood home of Vicky Curry, first cousin of Peter’s late mother, Mimi.

They asked him about his family’s religion (Sunni Islam), whether the school he taught at is still there (he’s not sure) and other questions.

“Have you experienced problems in Eugene?” asks Curry, a Eugene psychologist. “Prejudice?”

“I don’t understand,” Ali says.

“Has anybody not been nice to you?” Ward says.

“I think they are very friendly,” he says of people he’s encountered in Eugene thus far.

They ask about his plans.

“I want to get a job, so I can get some money to pay for my classes,” Ali says. “Then I want to transfer my degree (to the UO), so I can (teach).”

As the conversation continues, the family’s love for Ali is obvious.

“I think it’s a gift, to me, to have Ali here,” Curry says.

Ward and Ali have surfed at the Oregon Coast, hiked in the Three Sisters Wilderness Area and danced at downtown Eugene venues.

“I can honestly say, and this is no knock to my brother, Matthew, but I think I’m going to have a brother for life,” Ward says.

Toward the end of the evening, Ali has tears in his eyes. He wipes them away.

“Peter and his family have helped me a lot,” he says the next day. “When you go to a new place, a new culture, it’s very hard. I now feel that I have family here. They are really good people.”

First place award for long-form feature writing in the 2016 “Best of the West” contest.

Mark Baker has been a journalist for the past 25 years. He’s currently the sports editor at The Jackson Hole News & Guide in Jackson, Wyo.