‘Eugene will be by next fall in a class by itself’

1907-1917

By Mark Baker

For The Register-Guard

The first decade of the 20th century was a booming time in Eugene and Lane County.

Eugene’s population almost tripled, going from 3,236 in 1900 to 9,009 in 1910, and the county increased from 19,604 to 33,783.

Willamette Street, where the Guard had several different office locations between Fourth and Eighth avenues in its first six decades, was often a muddy mess when it rained, which of course was often in Western Oregon. Thus, the first paving of Willamette Street in 1907 was not only a godsend for residents, but a sign of the progress to come.

Electric trolley service was then added on the main thoroughfare, joining the motor cars that were also now making their way around town.

“Eugene Becomes a City,” read the headline of a June 1, 1907, editorial in the Eugene Daily Guard, after construction had begun.

“With Willamette Street paved from the depot to 11th Street, and electric cars upon it, Eugene will be by next fall in a class by itself so far as other Oregon towns outside of Portland are concerned,” the paper opined. “There will be no finer street in a Western city than our main business thoroughfare, and we predict that the property owners along several intersecting streets, especially Eighth and Ninth, will insist upon paving before the year is over.”

The Eugene Public Library opened in 1908 and voters that same year approved a $300,000 bond to buy the private water system in town, which became the Eugene Water & Electric Board in 1911.

The push for EWEB came as political aftermath of a 1906 typhoid epidemic, traced to the private water system. The Guard supported municipal ownership while The Morning Register opposed it, and both papers were filled from 1905 to 1908 with arguments for and against.

And the arguments arose again in 1910 when voters were asked to pass another bond measure to add a filtration system to purify the city’s water, then pumped from the Willamette River, before EWEB’s launch, but some thought it was too much.

“The people must either be willing to pay the price or else stop their talk about building up a city in Eugene,” the Guard opined on May 10, 1910. “If they are going to balk because growing population must be provided for by laying new water mains, by improvement of streets, and because it costs money to meet the growing expense of a greater municipality, then they should stop advertising the city, dissolve their booster organizations and quit. If, however, we purpose to build a city here the proper way to do [sic] is to keep up the program of public improvements and let increasing population and wealth pay off the bonds in the future.

The water filtration measure passed easily on May 16, 1910 – 628 to 227.

The University of Oregon also was asking the public for money around this time through a state referendum in 1911. Former President Teddy Roosevelt even came to town to stump for the university.

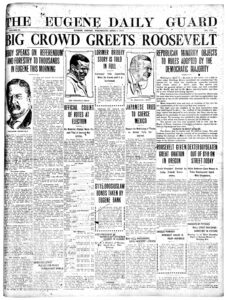

“Big Crowd Greets Roosevelt,” read the banner headline atop the April 5, 1911, front page.

Between 5,000 and 6,000 turned out to hear Roosevelt speak from the rear of his train car at the Eugene train depot.

“I’m so glad to be here to say a special word about and for the University of Oregon,” Roosevelt said. “In the east we are accustomed to look upon Oregon as a progressive state. And Oregon has taken the lead in more progress. But if Oregon goes back on her state university she will show herself, just to that degree, a retrogressive state.”

The state Legislature appropriated the money, but the 1902 ballot measure that created Oregon’s initiative and referendum process a decade earlier came back to haunt the UO in November 1912, as state voters overwhelmingly (73 percent to 27 percent) voted down the Oregon Appropriations for the University of Oregon Act that would have provided $175,000 for building and maintaining an administration building, and $153,000 for additional land and equipment and to pay salaries.

That four men were arrested in 1911 and charged with forging names on some of the referendum petitions, according to various news reports of the day, certainly didn’t help the cause.

But Johnson Hall, the UO’s administration building, was built for $104,000 in 1914-15 after the Legislature finally passed five appropriations bills totaling $318,000 for the UO in February 1913.

At the Eugene Daily Guard in 1913, Charles Fisher, who had purchased and run the paper since 1906, decided to sell, meaning the 46-year-old business would once again have new ownership.

Fisher sold to E.J. Finneran, who had high aspirations for the Guard. He expanded the floor space at the building the Guard was then renting at 458 Willamette St., and bought a Duplex tubular press capable of printing 30,000 16-page papers an hour.

However, financial problems that affected the economy after the start of World War I in 1914 left Finneran overextended, according to Warren Price’s book, and he incurred $20,000 of debt.

In January 1916, two men representing the building the Guard was renting filed a lawsuit. A receivership was established and the court appointed an “investment man,” E.J. Adams, to operate and control the Guard on Jan. 29, Price wrote.

Adams controlled the Guard for just three months. Fisher, who had moved to Salem and bought the ailing Capital-Journal, came to the Guard’s rescue once again and repurchased it, appointing Joseph Shelton, the Guard’s former advertising manager, who had left to become news editor at the Register, to run things until he returned in 1919.

Mark Baker, who researched and wrote the stories for this special section, is a former Register-Guard reporter and a member of the third generation of the Baker family.

Mark Baker has been a journalist for the past 25 years. He’s currently the sports editor at The Jackson Hole News & Guide in Jackson, Wyo.